Refer:

COP Themes.

See also:

Communities of practice – a brief introduction (Wenger et al., 2006).

'Our World as a Learning System'

From: Snyder, W. M. and Wenger, E. (2000) 'Our World as a Learning System: A Communities-of-Practice Approach', in Blackmore (ed.)

Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, London, Springer, ch. 7. (T1, T2, T3)

"think globally and act locally"; local civic engagement with active stewardship at national and international levels" (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 108).

Design Requirements for a World Learning System (T1, T2, T3):

- action-learning capacity [praxis]

- cross-boundary participation

- cross-level linkages

(Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 108-)

"focus on the underlying learning capacity" (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 109).

Cultivating learning systems (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 109-):

Depends on "professional identity", "informal learning" and "collegial relationships"

"A community's effectiveness as a social learning system depends on its strength in all three structural dimensions";

domain passion (with sufficient "specificity", aka Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 116),

community quality, diversity and leadership (i.e. coordination and core group) and

practice, from framework to methods (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 110) (T1, T2).

Varied dimensions of activities, "instrumental" and facilitating "presence" in members' lives (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 110) (T2).

i.e.;

- complement formal structures

- voluntary; based on passion

- self-governing

- (but can be organisationally "cultivated", but with an "evolutionary design process", a "two-system" result).

(Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 110-2) (T1, T2).

For example, "the city", "re-imagined as a learning system, consists of a constellation of cross-sector groups that provide stewardship for the whole round of civic domains", feeding into higher-level practice, "fractal"-like (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 114); "coalescing communities of practice ... the foundation for building relationships, generating ideas, and catalysing business initiatives", growing from "networking" and "personal" development to "promote" and "knowledge transfer" (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 115) (T1).

Strong stewardship of civic issues ... depends on vital communities of practice"; "networking", "professional development", "shared know-how" and "advocating" (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 115).

Key factors / strengths; coordination, peer-to-peer learning and cross-collaboration (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 118)

'Process' (cf. Ayuda Urbana, Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 119) (T1, T2);

- Initial development of relationships and trust, face-to-face.

- Participants share experiences.

- Participant discussion.

- Prioritise issues.

- Work out tools e.g. web-based.

- Choose coordinator.

This highlights the "importance of a skilled convener who is committed to a community-based practice approach" (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 120) (T1, T2).

The Fractal Structure of Large-Scale Learning Systems:

For scale;

"The principle to apply is that of a fractal structure (see Gleich, 1987; Wheatley, 1994). In such a structure, each level of substructure shares the characteristics of the other levels. Applying such a design principle, it is possible to preserve a small-community feeling while extending a system from the local to the international level." ... "The idea is to grow a ‘community of communities’ in which each level of sub-communities shares basic characteristics: focal issues, values, and a practice repertoire. " (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 120) (T1,T2,T3)

"The key insight of a fractal structure is that crucial features of communities of practice can be maintained no matter how many participants join – as long as the basic configuration, organising principles, and opportunities for local engagement are the same. "

- exponential advantages of scale

- but at the"time-scale of social relationships"; "be careful not to scale up too fast", build "trust and shared values"

(Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 121) (T1)

i.e. "advantage of ... evolutionary" (Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 123) (T1)

Each dimension of COP "provides opportunities for the constitution of a fractal learning system";

fractal domain sub-division, multimembership in fractal communities; "local intimacy" but interconnected; trust networks., fractal practice with "shared repertoire" of "overall learning system" but with local adaptation.

(Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 120-1) (T1, T2, T3)

Challenges for civic learning systems: sponsorship [resourcing?], process [and admin] support, conflict resolution and collaborative inquiry (conflict and power issues), [and] need for COP framework (a "discipline of world design"), with meta-communities of practice. This is about a "transformation of civic consciousness". Also, "remaining on a learning edge", requiring COP and individual dynamics (cf. (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 182).

(Snyder and Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 122-3) (T1, T3)

Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems

From: Wenger, E. (2010) 'Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: the Career

of a Concept', in Blackmore (ed.)

Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, London, Springer, ch. 11. (T1, T2)

A Social Systems View on Learning:

Communities of Practice as Social Learning Systems, exhibiting "characteristics of systems", a "social structure" of "participation" and "artefacts" (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 179-).

Learning as the production of social structure: A "practice is ... produced over time by those who engage in it, regardless of constraints or functionality, a practice "has a life of its own"- it "cannot be subsumed by a design", i.e. "the property of the community" (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 180-181).

-balanced by-

Learning as the production of identity

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 181-182)

A Learning View on Social Systems:

Communities of Practice in (larger) Social Learning Systems

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 182-).

Learning as the Structuring of Systems: Landscapes of Practice

"Boundaries are interesting places"; "boundary processes require careful management"

"There is therefore a profound paradox as the heart of learning in system of practices: the learning and innovative potential of the whole system lies in the coexistence of [local] [and individual, aka Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 181] depth within practices and active boundaries across practices."

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 182-4).

Modes of Identification: engagement, imagination, alignment.

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 184-185).

Identity in a Landscape of Practices

"Learning can be viewed as a journey through landscapes of practices. Through engagement, but also imagination and alignment, our identities come to reflect the landscape in which we live and our experience of it. Identity itself becomes a system, as it were."

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 185).

- Identity is a trajectory

- Identity is a nexus of multimembership

- Identity is multi-scale

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 185).

"Through learning, ... communities [etc] ... become part of who we are. Identities become personalised reflections of the landscape of practices. Participation in social systems is ... the constitutive texture of an experience of the self."

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 186).

"identity is both collective and individual" (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 186).

Knowledgeability as the (complex) Modulation of Accountability (among multiple contexts)

Identification is ... negotiating and something others do to us. Sometimes the result is an experience of participation; sometimes of non-participation." (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 186).

"The regime of competence of a community of practice translates into a regime of accountability", that is "hard work", a "dance of the self' (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 186-7).

i.e. "a constant interplay between practices and identities" (Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 187).

Critiques

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 188-).

What about Power? Conflict and context?

Economies of Meaning: The "definition of the regime of accountability and ... claim[s] to competence", 'invisible' power forms, and power through "reification", identification opens "vulnerability" to power, power in learning theory; inherently political; "local production implies a notion of agency in the negotiation of meaning, which even the most effective power cannot fully subsume"; the "optimistic" "crack of agency in the concrete of social structure", power as learned relations.

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 188-191).

Anachronistic? v. network?

v. the needs of "modern", "dynamic structures".

Network and community as "complementary"; "identity" and "connectivity".

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 191-2).

A Co-opted Concept: On the Instrumental Slippery Slope?

The danger of "design intention" vs. grassroots, to be "more effective" but without "profound transformation".

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 192).

"Good in theory, but difficult to apply in practice" (within traditional hierarchical organisation)

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 192-3).

See also:

Gobbi (2009) "Professional practice" as (ontologically and epistemologically) different., "society" and "leadership". Note: Effects [on COPs] of client/service structure and formal factors [if relevant] (Gobbi, 2009, in Blackmore, 2010, ch. 10).

Towards a Social Discipline of Learning

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 193-).

Practice: Learning Partnerships

- "The concept of community of practice is a good place to start exploring a social discipline of learning."; "simple"

- The disciplines of domain, community, practice and convening.

- There may be harmony or conflict, but overall "trust in the learning capability of a partnership".

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 193-194).

Learning Governance: Stewardship and Emergence

- Stewarding [directed] governance.

- Emergent [from "distributed"] governance.

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 194-195).

Power: [Both] Vertical and Horizontal Accountability:

Complementary advantages and disadvantages.

Transversality processes and roles: the ability to increase the visibility and integration between vertical and horizontal structures.

(cf. Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 195-196).

Identity: Learning Citizenship: managing memberships, brokering boundaries, convening, connecting others, facilitating transversal connections

- "challenging us to see ourselves as the learning contribution we have to offer"

(Wenger, 2010, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 196-197).

Conceptual Tools for CoPs

From: Wenger, E. (1998/2000) 'Conceptual Tools for CoPs as Social Learning Systems: Boundaries, Identity, Trajectories and Participation', in Blackmore (ed.) Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, London, Springer, ch. 8.

Fluid boundaries, connect communities, learning at boundaries, experience and competence in tension (Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 125-127)

Dimensions of boundary effects; Coordination, Transparency, Negotiability (Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 127).

"Bridges across boundaries" (Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 127-130); brokering, boundary objects (artefacts, discourse language, processes), boundary interactions (encounters, boundary practices specialisations and peripheries).

-> Cross-Disciplinary Projects (Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 130-).

-> Landscape(s) of Practice; practice as “informal” i.e. “organic” (vs. institutional boundaries), Boundaries vs. Peripheries (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 130-).

("Ongoing", temporal") Identity in Practice: as negotiated experience, as community membership, as learning trajectory, as nexus of multimembership, as a relation between the local and the global (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 133-134); cf. “Reconciliation” (of engaging, accountability and repertoire) of "Nexus of Multimembership" (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 137-); a "weaving" (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 139)

-> (negotiated) "Paradigmatic Trajectories" (for identity), including the "history", "people" and the "story" /"narrative" (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 135-) -> Generational Encounters (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 136-).

Social Bridges and Private Selves;

"Multimembership is the living experience of boundaries. This creates a dual rela tion between identities and the landscape of practice: they reflect each other and they shape each other. In weaving multiple trajectories together..."; "Even though each element of the nexus may belong to a community, the nexus itself may not. The careful weaving of this nexus of multimembership into an identity can therefore be a very private achievement."

(Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 139).

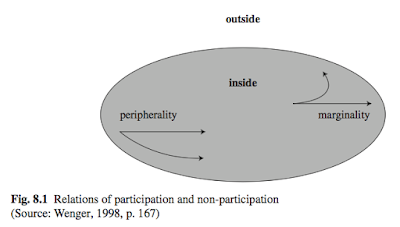

See: Participation and Non-participation; peripherality and marginality (Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 140-);

(From Wenger, 1998, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 142).

"For communities of practice, it requires a balance between core and boundary processes," (Wenger, 2000, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 142).

References / readings

Snyder, W. M. and Wenger, E. (2000) 'Our World as a Learning System: A Communities-of-Practice Approach', in Blackmore (ed.)

Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, London, Springer, ch. 7. (T1, T2, T3)

Wenger, E. (1998/2000) 'Conceptual Tools for CoPs as Social Learning Systems: Boundaries, Identity, Trajectories and Participation', in Blackmore (ed.)

Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, London, Springer, ch. 8.

Wenger, E. (2010) 'Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: the Career

of a Concept', in Blackmore (ed.)

Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, London, Springer, ch. 11. (T1, T2)